Discussion 10. Causal Effects with Regression Discontinuity

NOTE: This is from Fall 2023. We have not updated to reflect the current term yet.

Slides Download today’s .Rmd document here.

13.11 Choosing a bandwidth

One of the main difficulties of a regression discontinuity analysis is choosing a ``good’’ bandwidth. This is a good example of the bias variance trade-off which appears all the time in statistics. In general, we will let the software choose this for us, but it will be helpful to run through a small example to better understand the subtleties involved.

Suppose \(Y\) is a very non-linear function of \(X\), and we want to extrapolate and predict \(Y\) at \(X=0\).

n <- 100

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

### Y is a very non-linear function of X + some noise

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

plot(X, Y, ylim = c(-15, 30), xlim = c(-5, 1))

abline(v = 0, col = "gray", lwd = 2)

### Avg Y when X = 0 is 5

points(0, 5, pch = 18, col = "orange", cex = 3)

If we blindly fit a line to all our observations, the predicted value for \(X=0\) is off by quite a bit.

If we instead restrict ourselves to a smaller region around 0, we can do a bit better

## Only consider points h away from 0

h <- 3

fit.mod.bandwidth <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h)

plotColor <- ifelse(abs(X) > h, "gray", "red")

plot(X, Y, ylim = c(-15, 30), xlim = c(-5, 1), col = plotColor)

abline(v = 0, col = "gray", lwd = 2)

segments(-h, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "blue",

lwd = 2)

points(0, 5, pch = 18, col = "orange", cex = 3) However, if we get more and more data, we don’t really improve much

However, if we get more and more data, we don’t really improve much

n <- 10000

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

h <- 3

fit.mod.bandwidth <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h)

plotColor <- ifelse(abs(X) > h, "gray", "red")

plot(X, Y, ylim = c(-15, 30), xlim = c(-5, 1), col = plotColor)

abline(v = 0, col = "gray", lwd = 2)

segments(-h, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "blue",

lwd = 2)

points(0, 5, pch = 18, col = "orange", cex = 3)

Ideally, we would decrease the bandwidth to reduce this bias, but this also means we are working with less data. Since each data point is noisy, if we were to get a new sample, the estimate could change quite a bit. Try running this a few times and see how much the estimate moves. Compare this which how much the estimate moves if the bandwidth is 2.

h <- .3 # bandwidth

# h <- 2

n <- 100

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

fit.mod.bandwidth <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h)

plotColor <- ifelse(abs(X) > h, "gray", "red")

plot(X, Y, ylim = c(-15, 30), xlim = c(-5, 1), col = plotColor)

abline(v = 0, col = "gray", lwd = 2)

segments(-h, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "blue",

lwd = 2)

points(0, 5, pch = 18, col = "orange", cex = 3)

points(0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)), col = "blue", pch = 19)

Knowing the best bandwidth is a hard problem, but generally speaking a good choice of bandwidth will get smaller as the sample size increases.

If we measure accuracy in terms of average squared error, we can see when \(n = 100\), a bandwidth of 1.2 seems to be best. However, test and see if how that changes for larger values of \(n\)

n <- 100

h <- c(.5, .8, 1.2, 2)

sim.size <- 500

rec <- matrix(0, sim.size, 8)

for(i in 1:sim.size){

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

fit.mod.bandwidth1 <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h[1])

fit.mod.bandwidth2 <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h[2])

fit.mod.bandwidth3 <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h[3])

fit.mod.bandwidth4 <- lm(Y~X, subset = X > -h[4])

rec[i, 1] <- (predict(fit.mod.bandwidth1, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)) - 5)^2

rec[i, 2] <- (predict(fit.mod.bandwidth2, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)) - 5)^2

rec[i, 3] <- (predict(fit.mod.bandwidth3, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)) - 5)^2

rec[i, 4] <- (predict(fit.mod.bandwidth4, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)) - 5)^2

rec[i, 5] <- predict(fit.mod.bandwidth1, newdata = data.frame(X = 0))

rec[i, 6] <- predict(fit.mod.bandwidth2, newdata = data.frame(X = 0))

rec[i, 7] <- predict(fit.mod.bandwidth3, newdata = data.frame(X = 0))

rec[i, 8] <- predict(fit.mod.bandwidth4, newdata = data.frame(X = 0))

}## Warning in predict.lm(fit.mod.bandwidth1, newdata =

## data.frame(X = 0)): prediction from rank-deficient fit;

## attr(*, "non-estim") has doubtful cases

## Warning in predict.lm(fit.mod.bandwidth1, newdata =

## data.frame(X = 0)): prediction from rank-deficient fit;

## attr(*, "non-estim") has doubtful cases

colMeans(rec)## [1] 9.308383 5.115590 3.554670 12.365731 5.074313

## [6] 4.981461 4.352593 1.789852

boxplot(as.list(data.frame(rec[, 5:8])), ylim = c(0, 20))

abline(h = 5, col = "red") ### Weighted Least Squares

### Weighted Least SquaresWhen we estimate a linear regression model, we usually pick linear coefficients to minimize the squared errors \[\min_b \sum_i(Y_i - X_i b)^2\] and the squared error for each observation count are considered equally. But if a good fit around some points is more important than other points, we can also use weighted least squares where \(w_i\) is a weight. \[\min_b \sum_i w_i(Y_i - X_i b)^2\] When \(w_i\) is larger, the squared error for observation \(i\) will cost more so the selected linear coefficient will prioritize minimizing errors where \(w_i\) is large. In our particular setting, we want to prioritize fitting the data well around \(0\), so we can use weights which are ``triangular’’ which prioritize points near \(0\).

n <- 200

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

weight <- 1 - abs(X) / 5

plot(X, weight, type = "p", main = "Triangular Weights")

13.11.0.1 Question

If we use a bandwidth of \(h\) (i.e., only include observations within \(h\) of the cut-off), what does this mean the the weights would be?

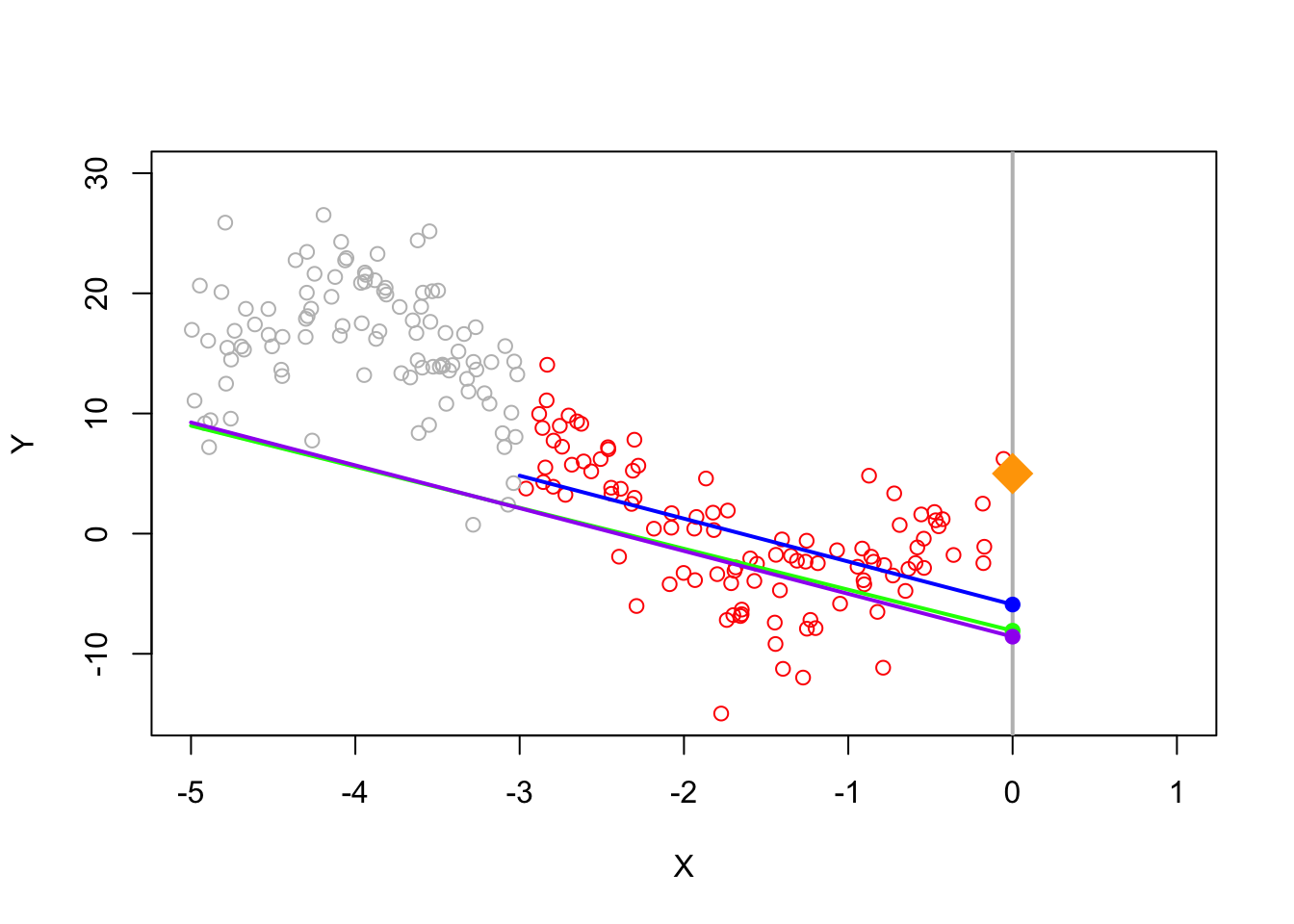

When using triangular weights, we can see that this does better than using all the points.

n <- 200

h <- 3

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

weight <- 1 - abs(X) / 5

# We don't include a bandwidth, but instead use triangular weights

fit.mod <- lm(Y~X)

fit.mod.weights <- lm(Y~X, weights = weight)

fit.mod.bandwidth <- lm(Y~X, subset = abs(X) < h)

plotColor <- ifelse(abs(X) > h, "gray", "red")

plot(X, Y, ylim = c(-15, 30), xlim = c(-5, 1), col = plotColor)

abline(v = 0, col = "gray", lwd = 2)

segments(-h, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "blue",

lwd = 2)

# Fit from weighted least squares

segments(-5, predict(fit.mod.weights, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod.weights, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "green",

lwd = 2)

# Fit from ordinary least squares

segments(-5, predict(fit.mod, newdata = data.frame(X = -h)),

0, predict(fit.mod, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)),col = "purple",

lwd = 2)

points(0, 5, pch = 18, col = "orange", cex = 3)

points(0, predict(fit.mod.bandwidth, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)), col = "blue", pch = 19)

points(0, predict(fit.mod.weights, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)), col = "green", pch = 19)

points(0, predict(fit.mod, newdata = data.frame(X = 0)), col = "purple", pch = 19) In practice, we can combine both a hard thresholding bandwidth as well as triangular weights (within the bandwidth)

In practice, we can combine both a hard thresholding bandwidth as well as triangular weights (within the bandwidth)

# bandwidth

h <- 3

n <- 200

X <- runif(n, -5, 0)

Y <- 5 - 3*X + .6 * X^2 + .3 * X^3 + 15 * sin(X) + rnorm(n, sd = 4)

# weight is triangular within the bandwidth

weight <- ifelse(abs(X) < h, 1 - abs(X) / h, 0)

plot(X, weight, type = "p", main = "Triangular Weights")

13.12 RDD Analysis

Now let’s apply a regression discontinuity analysis to data. This example follows the analysis ``Randomization Inference in the Regression Discontinuity Design: An Application to Party Advantages in the U.S. Senate’’ by Cattaneo, Frandsen, and Titiunik (2015) and their replication file.

Political scientists are interested in the effect of being an incumbent (the currently elected politician) on the share of votes in an election. Being the current public official means increased name recognition, fundraising opportunities, etc. On the other hand, being an incumbent means you can get blamed for all the bad things that have happened during your term.

The data we analyze considers US senators. Each state in the US has two senators with 6 year terms, and the election for each of the two senators alternates every 3 years. So for instance, there are two senate seats: A and B. In 2000 senate seat A undergoes an election, in 2003 senate seat B undergoes an election but senate seat A continues, in 2006 senate seat A undergoes an election but senate seat B continues on, etc.

We will look at the causal effect on being an incumbent in senate races in two different ways.First, does being an incumbent effect your vote share the next time you run for office? Second, if the other sitting senator is from your same party, what is the effect on your election share?

13.12.0.1 Question

- Consider the first question and draw out a causal diagram where the treatment is being an incumbent and the outcome of interest is vote share in an election.

- How might we use regression discontinuity to provide an answer to this question?

13.12.1 Data

We’ll examine data from US Senate races from 1914 to 2010 to try and answer these questions.

install <- function(package) {

if (!require(package, quietly = TRUE, character.only = TRUE)) {

install.packages(package, repos = "http://cran.us.r-project.org", type = "binary")

library(package, character.only = TRUE)

}

}

install("ggplot2")

install("lpdensity")

install("rddensity")

install("rdrobust")

install("rdlocrand")

data <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/rdpackages-replication/CIT_2020_CUP/master/CIT_2020_CUP_senate.csv")

head(data)## state year dopen population presdemvoteshlag1

## 1 Connecticut 1914 0 1233000 39.15937

## 2 Connecticut 1916 0 1294000 39.15937

## 3 Connecticut 1922 0 1431000 33.02737

## 4 Connecticut 1926 0 1531000 27.52570

## 5 Connecticut 1928 1 1577000 27.52570

## 6 Connecticut 1932 0 1637000 45.57480

## demmv demvoteshlag1 demvoteshlag2 demvoteshfor1

## 1 -7.6885610 NA NA 46.23941

## 2 -3.9237082 42.07694 NA 36.09757

## 3 -6.8686604 36.09757 46.23941 35.64121

## 4 -27.6680560 45.46875 36.09757 45.59821

## 5 -8.2569685 35.64121 45.46875 48.47606

## 6 0.7324815 45.59821 35.64121 51.74687

## demvoteshfor2 demwinprv1 demwinprv2 dmidterm dpresdem

## 1 36.09757 NA NA 1 1

## 2 45.46875 0 NA 0 1

## 3 45.59821 0 0 1 0

## 4 48.47606 0 0 1 0

## 5 51.74687 0 0 0 0

## 6 39.80264 0 0 0 0

# presdemvoteshlag1 is democratic vote share in the previous presidential election

# demmv is the democratic margin of victory in the current senate election (i.e., democratic percentage - next closest percentage)

# so a value just above 0 indicates a very close victory, a value just below 0 indicates a very close loss

# demovoteshlag1 and 2 indicates the vote share 1 and 2 election cycles ago

# demovoteshfor1 and 2 indicates the vote share 1 and 2 elections cycles in the futureFor the first analysis, we will consider whether being the incumbent effects vote share in the next election. Thus, the outcome of interest is because the next time the same seat goes up for election is 2 cycles in the future.

dem_vote_t2 <- data$demvoteshfor2

dem_margin_t0 <- data$demmv

# plot the data

# Set p = 0 for a straight line (i.e., regression with X^p)

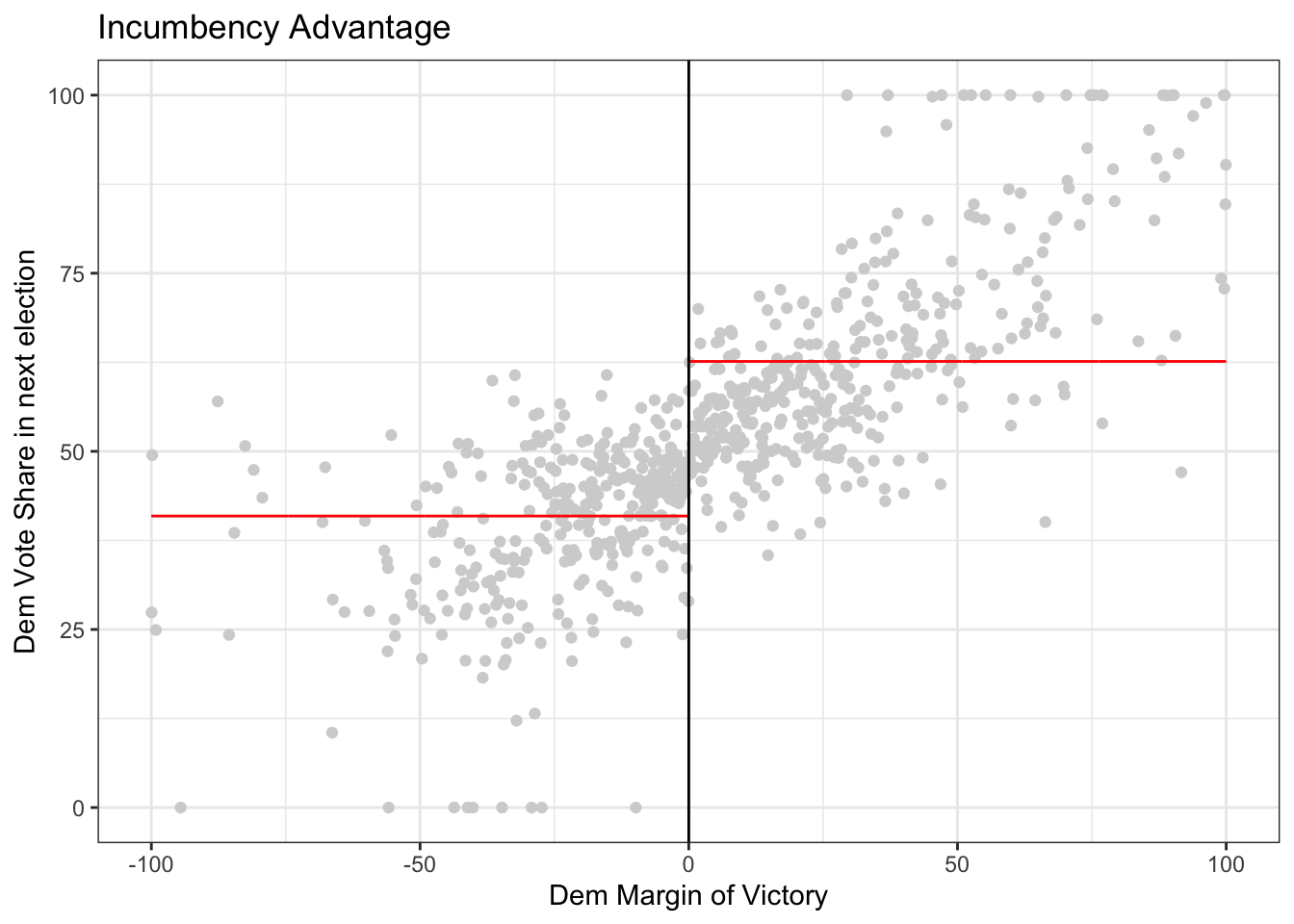

rdplot(y = dem_vote_t2, x = dem_margin_t0, nbins = c(1000, 1000), p = 0, col.lines = "red", col.dots = "lightgray", title = "Incumbency Advantage", y.lim = c(0,100), x.label = "Dem Margin of Victory", y.label = "Dem Vote Share in next election")

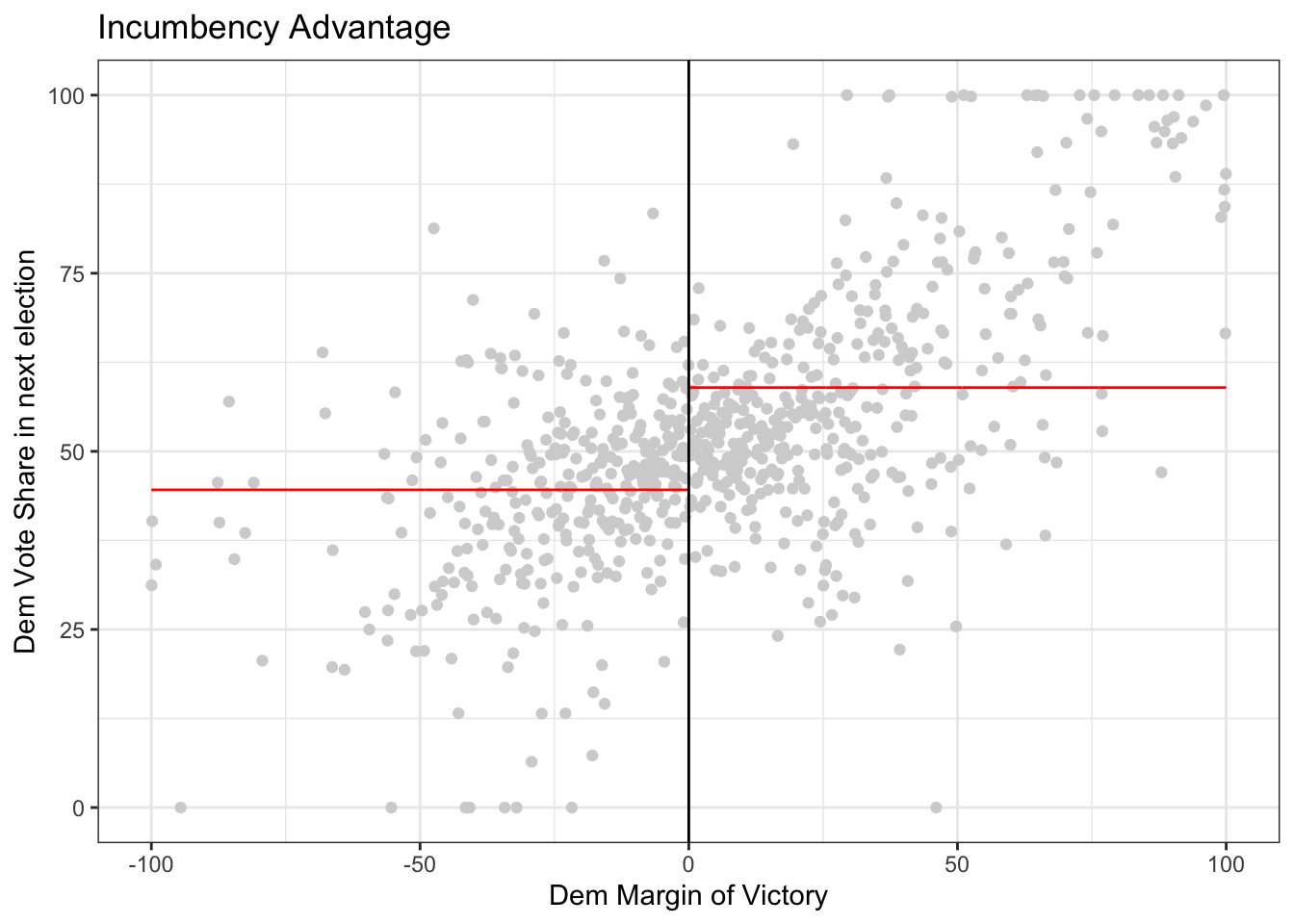

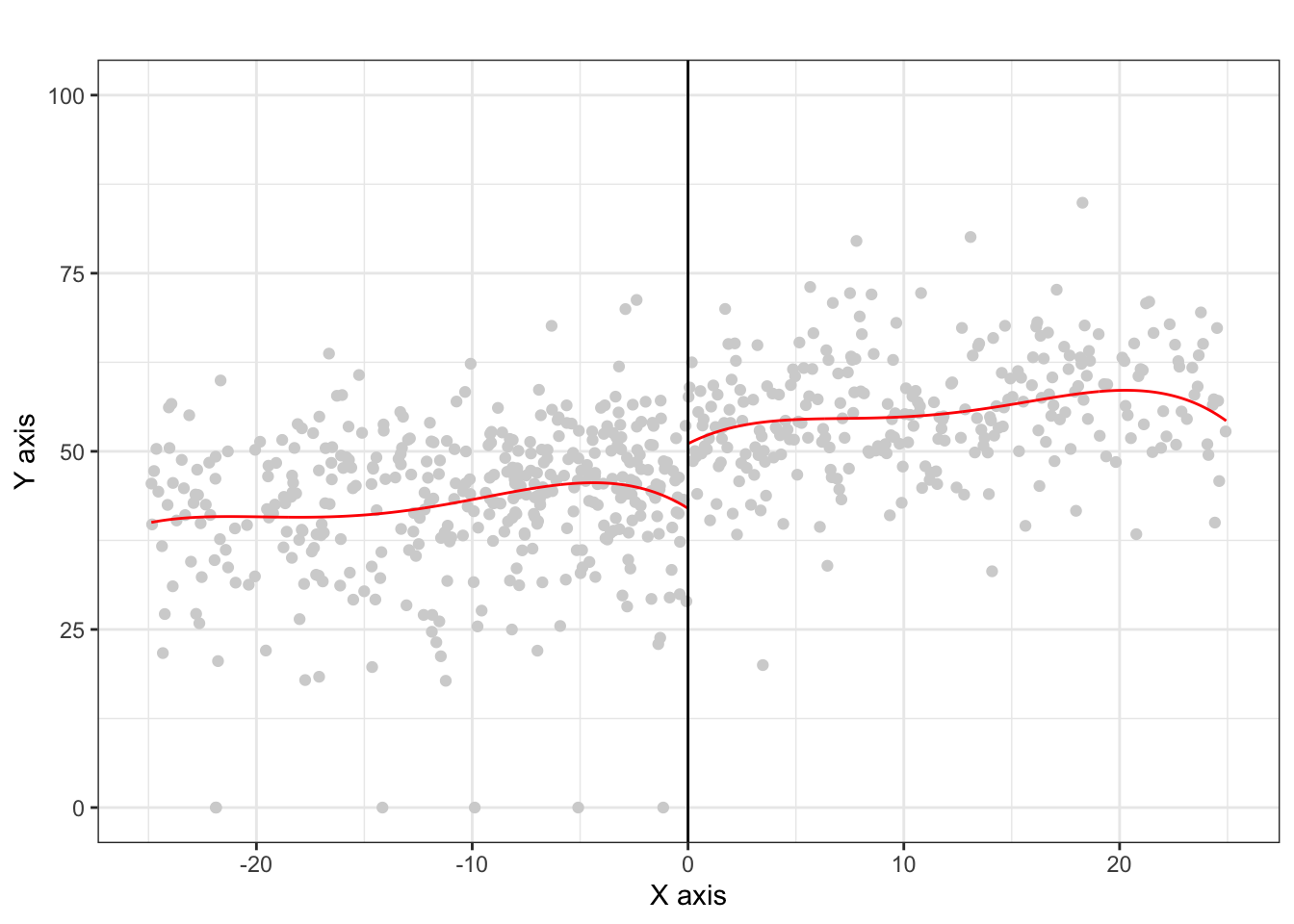

Let’s zoom in a bit to the closer races and use non-linear regression. There appears to still be a slight discontinuity.

rdplot(dem_vote_t2[abs(dem_margin_t0) <= 25], dem_margin_t0[abs(dem_margin_t0) <= 25], nbins = c(2500, 500), p = 4, col.lines = "red", col.dots = "lightgray", title = "", y.lim = c(0,100))

13.12.2 Estimating the causal effect

As an example, we’ll manually set the bandwidth to 10, and then estimate a linear regression on both sides of the cut-off. The estimated intercept is the prediction at \(0\), so to get the estimate, we just take the difference.

# Set bandwidth to 10

h <- 10

# Fit regression to left and right of cut-off

lm_left <- lm(dem_vote_t2 ~ dem_margin_t0, subset = dem_margin_t0 < 0 & abs(dem_margin_t0) <= h)

lm_right <- lm(dem_vote_t2 ~ dem_margin_t0, subset = dem_margin_t0 > 0 & abs(dem_margin_t0) <= h)

# Estimate is difference in interecepts

lm_right$coefficients[1] - lm_left$coefficients[1] ## (Intercept)

## 6.898794We can try the same with the triangular weights.

h <- 10

weight <- ifelse(abs(dem_margin_t0) < h, 1 - abs(dem_margin_t0) / h, 0)

## Note we don't need subs

lm_left <- lm(dem_vote_t2 ~ dem_margin_t0, subset = dem_margin_t0 < 0 & abs(dem_margin_t0) <= h, weights = weight)

lm_right <- lm(dem_vote_t2 ~ dem_margin_t0, subset = dem_margin_t0 > 0 & abs(dem_margin_t0) <= h, weights = weight)

# Estimate is difference in interecepts

lm_right$coefficients[1] - lm_left$coefficients[1] ## (Intercept)

## 7.98468713.13 Using rdrobust

As you can see, getting the estimates aren’t so difficult once we’ve selected a bandwidth. But selecting a good bandwidth can be tricky and getting standard errors on the estimate are also difficult. We can use the R package to select the bandwidth, estimate the causal effect quantities, and give standard errors.

# uniform kernel with bandwidth 10

out <- rdrobust(dem_vote_t2, dem_margin_t0, kernel = 'uniform', p = 1, h = 10)

summary(out)## Sharp RD estimates using local polynomial regression.

##

## Number of Obs. 1297

## BW type Manual

## Kernel Uniform

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 595 702

## Eff. Number of Obs. 245 206

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 10.000 10.000

## BW bias (b) 10.000 10.000

## rho (h/b) 1.000 1.000

## Unique Obs. 595 702

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 6.899 1.722 4.007 0.000 [3.525 , 10.273]

## Robust - - 3.891 0.000 [5.156 , 15.624]

## =============================================================================

# triangular kernel with bandwidth 10

out <- rdrobust(dem_vote_t2, dem_margin_t0, kernel = 'triangular', p = 1, h = 10)

summary(out)## Sharp RD estimates using local polynomial regression.

##

## Number of Obs. 1297

## BW type Manual

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 595 702

## Eff. Number of Obs. 245 206

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 10.000 10.000

## BW bias (b) 10.000 10.000

## rho (h/b) 1.000 1.000

## Unique Obs. 595 702

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 7.985 1.838 4.344 0.000 [4.382 , 11.587]

## Robust - - 4.387 0.000 [6.595 , 17.249]

## =============================================================================If we don’t specify a bandwidth directly, the software will choose for us

# uniform kernel with software selected bandwidth

out <- rdrobust(dem_vote_t2, dem_margin_t0, kernel = 'triangular', p = 1)

summary(out)## Sharp RD estimates using local polynomial regression.

##

## Number of Obs. 1297

## BW type mserd

## Kernel Triangular

## VCE method NN

##

## Number of Obs. 595 702

## Eff. Number of Obs. 360 323

## Order est. (p) 1 1

## Order bias (q) 2 2

## BW est. (h) 17.754 17.754

## BW bias (b) 28.028 28.028

## rho (h/b) 0.633 0.633

## Unique Obs. 595 665

##

## =============================================================================

## Method Coef. Std. Err. z P>|z| [ 95% C.I. ]

## =============================================================================

## Conventional 7.414 1.459 5.083 0.000 [4.555 , 10.273]

## Robust - - 4.311 0.000 [4.094 , 10.919]

## =============================================================================13.13.1 Try on your own

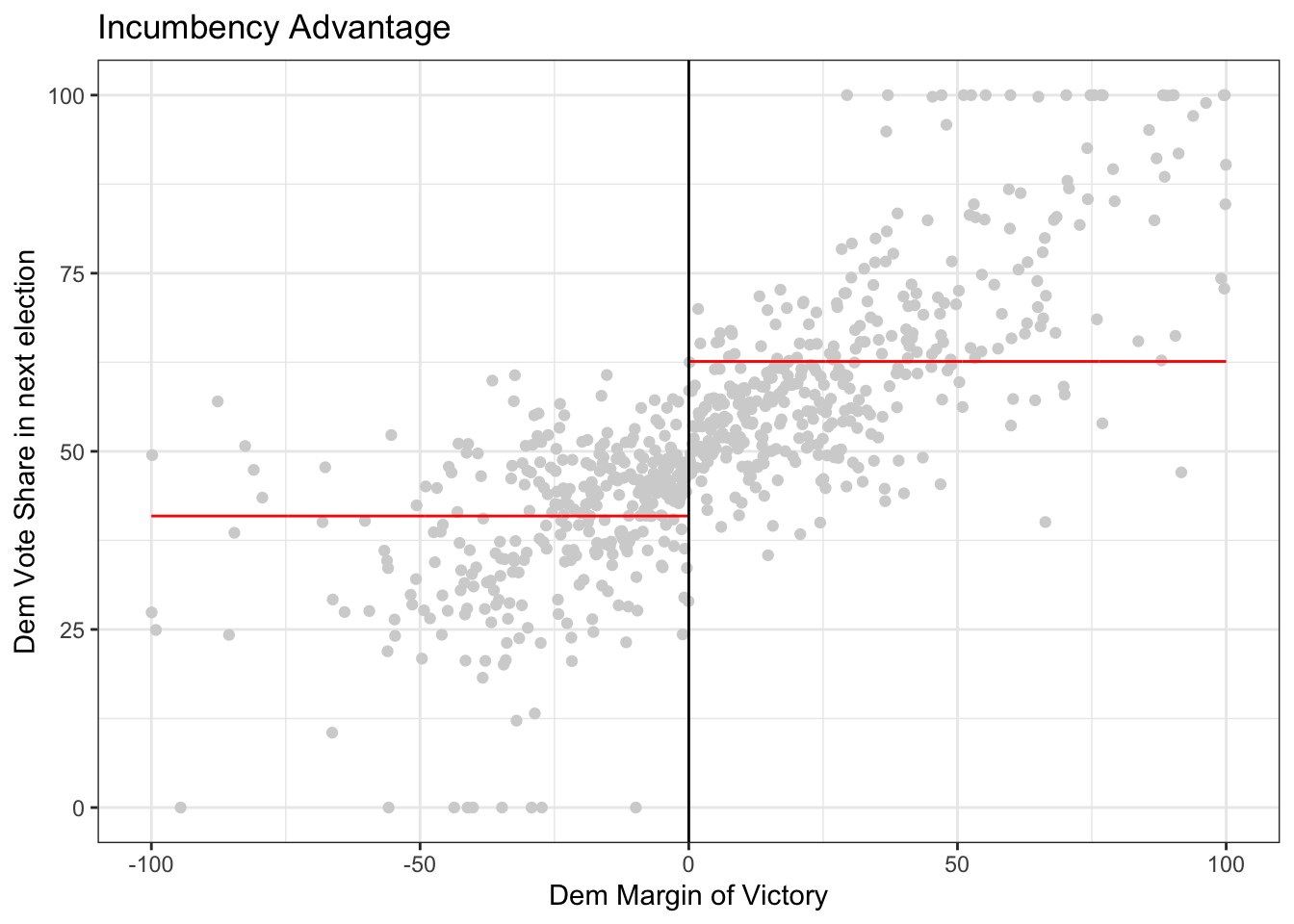

Now try on your own and estimate the causal effect of the senator who is not up for election being a democrat on the democratic vote share of the senator who is up for election. In this case, the outcome of interest is demvoteshfor1 since we are interested in the immediately following election.

dem_vote_t1 <- data$demvoteshfor1

dem_margin_t0 <- data$demmv

# plot the data

# Set p = 0 for a straight line (i.e., regression with X^p)

rdplot(y = dem_vote_t1, x = dem_margin_t0, nbins = c(1000, 1000), p = 0, col.lines = "red", col.dots = "lightgray", title = "Incumbency Advantage", y.lim = c(0,100), x.label = "Dem Margin of Victory", y.label = "Dem Vote Share in next election")